- Teach staff about typical development of language and literacy skills across childhood.

- Model enriching language and literacy practices.

- Observe and provide feedback on ways staff members promote language development and communication.

Learn

Teach

Ages and Stages of Language and Literacy Development

It is your role to help staff members understand the critical elements of child development. This lesson provides a brief overview of how communication develops from birth through age 12. Staff members have read similar information in their own lessons, so this is intended to provide you with consistent information and terminology. The information and resources are intended as a reference for you or as something you can provide to staff members as a refresher.

Infant and Toddler Milestones

Infants’ and toddlers’ abilities to communicate grow as they interact and communicate with others. In fact, the sounds, tones, and patterns of speech that an infant hears early on sets the stage for learning a specific language. They begin to understand words, express themselves using words, and learn the rules of conversation in their language.

You will help staff members understand these milestones. Staff received a chart about infant and toddler development in their own lessons. It’s important that you help them keep in mind that individual differences exist when it comes to the specific age at which infants and toddlers meet milestones; each child is unique. As highlighted in the Cognitive and Physical courses, milestones provide a guide for when to expect certain skills or behaviors to emerge. Here is a reminder about general language and communication developmental milestones:

Language and Communication Milestones in Infants & Toddlers

6 Months

- Responds to sounds by making sounds

- Strings vowels together when babbling (“ah,” “eh,” “oh”) and takes turns while making sounds

- Responds to own name

- Makes sounds to show joy and displeasure

- Begins to say consonant sounds (jabbering with “m,” “b”)

12 Months

- Responds to simple spoken requests

- Uses simple gestures like shaking head “no” or waving “bye-bye”

- Makes sounds with changes in tone (sounds more like speech)

- Says “mama” and “dada” and exclamations like “uh-oh!”

- Tries to say words you say

18 Months

- Says several single words

- Says and shakes head “no”

- Points to show someone what he wants

24 Months

- Points to things or pictures when they are named

- Knows names of familiar people and body parts

- Says sentences with 2 to 4 words

- Follows simple instructions

- Repeats words overheard in conversation

- Points to things in a book

Preschool Milestones

You should help staff members understand how children continue to develop during the preschool years. Staff will use the chart in the Apply Section for an understanding of how preschoolers communicate. You can review the chart as a reminder of the content. It’s important to help staff keep in mind that that each child is unique and individual differences exist when it comes to the precise age at which children meet these milestones.

Language and Communication Milestones in Preschool-Age Children

Age 3

- Follows instructions with 2 or 3 steps

- Can name most familiar things

- Understands words like “in,” “on,” and “under”

- Says first name, age, and sex

- Names a friend

- Talks well enough for strangers to understand most of the time

- Says words like, “I,” “me,” “we,” and “you” and some plurals (cars, dogs, cats)

- Carries on a conversation using 2 to 3 sentences

Age 4

- Tells stories

- Sings a song or says a poem from memory, such as the “Itsy Bitsy Spider” or the “Wheels on the Bus”

- Knows some basic rules of grammar, such as correctly using “he” and “she”

- Can say first and last name

- Asks questions and provides explanations

Age 5

- Speaks very clearly

- Tells a simple story using full sentences

- Uses future tense; for example, “Grandma will be here.”

- Says name and address

- Knows and may misapply rules of grammar (i.e., says “goed” instead of “went”)

- Begins using “private speech”; you might hear the child’s inner monologue

- Can define common items by use (i.e., a fork is a thing you eat with)

School-Age Milestones

As you know, the school-age years are full of rich development in how children use language and develop literacy skills. Communication skills are vital to interacting and participating in all aspects of a child’s environment. School-age children will be exploring and expanding on the four major components of communication, which are listening, talking, reading and writing. You will help staff members understand this important stage and how to nurture development. You can find a guide in the Apply section for more depth about how and when school-age children develop important communication skills.

How Children Communicate

As you study the charts above and in the attachment, you will notice that some milestones are associated with children’s ability to listen to and understand language (receptive communication), others with children’s ability to express themselves using sounds, movements, gestures, facial expressions and words (expressive communication), and others with their knowledge and ability to engage in communication exchanges with peers or adults (social engagement). Let’s take a look at how these aspects of communication unfold and as part of the remarkable development of young children from birth to age 12.

Receptive Communication

Receptive communication refers to children’s ability to listen to and understand language. Infants begin to understand language as part of their nurturing relationships with responsive, trusted adults and are able to make sense of gestures, facial expressions and words well before they are able to verbally express themselves. During the preschool years, language comprehension increases dramatically. Children begin to understand more words, longer sentences, and more elaborate questions. They understand the names of most things in their daily environment (nouns for persons, pets, or things they see or use each day, such as mom, dad, dog, cat, shoes, ball) and actions they see or engage in each day (verbs such as running, hopping, drinking, or jumping). Children also begin to learn new descriptive words (adjectives such as soft, hard, or smooth), and emotion words (e.g., mad, sad, happy, scary).

Understanding language is closely related to young children’s cognitive development. Three-year-olds begin to use and understand “why,” “when,” and “how” questions. By the time they are 4, children understand many words for colors, shapes, and sizes. Understanding language is also closely related to early literacy math skill development. During the fourth year, children are learning to understand letter names and sounds and number names and meaning. Receptive language is essential for success in preschool, as children need to understand how to follow directions, and listen to what teachers, other significant adults in their lives, or peers have to say.

As children move through the school-age years, their ability to remember information, respond to instructions, and follow sequences of information improves. They begin developing the ability to draw conclusions from what they hear and to form opinions.

Expressive Communication

Expressive communication is the ability for children to express themselves through sounds, gestures, facial expressions and words. A beginning point for expressive communication is the infant’s cry. Cooing is another form of early communication and can begin as early as one month. By six-months, you can hear new sounds like “ma,” “ba,” and “da.” By 18-months, you may hear toddlers using two- and three-word sentences, such as “me go,” or “more drink, please.”

Preschool children learn to use new words every day. They use these new words in conversations and social interactions with peers and adults in their lives. Preschool children use expressive language throughout their day. They talk about their actions, emotions, needs, and ideas. They also respond to what others are saying. This becomes particularly apparent when you watch children playing with each other. They often talk about what they are playing with, describe their actions and ideas for play, and respond to what their friends are saying and doing. These examples highlight how oral language is closely related to social development. However, sometimes children also use expressive language to engage in private speech. Children may talk to themselves when they are engaged in difficult tasks, to think out loud, or when they are excited. For example, a child may talk to herself while she is building a high tower with blocks (e.g., saying things like “one more, don’t fall”) or when she completes a new or challenging activity (e.g., “I finished the big puzzle all by myself!”).

School-age children are sophisticated speakers. The youngest school-age children are understood by most people, can answer simple questions, retell stories, and participate actively in conversations. As they grow, they develop the ability to express ideas in clear and complete sentences, give directions, clarify and explain ideas, summarize, and use language for a variety of purposes.

Social Engagement

Social engagement involves the understanding and use of communication rules such as listening, taking turns, and using appropriate sounds and facial expressions. Conversations involve both understanding (receptive communication) and expressing (expressive communication). Infants and toddlers learn the ways to use sounds, gestures, facial expressions and words of their family’s language when adults interact, talk, read or sing with them.

As children grow, social engagement becomes equated with conversation skills. Conversations involve both understanding language (receptive communication) and speaking (expressive communication). Conversation skills involve learning to take turns, listening, speaking, and maintaining interest in a topic. Preschool children begin having conversations with adults and eventually learn to carry out conversations with peers. By school-age, most children carry on complex conversations and can enter and exit conversations appropriately.

Helping Staff Members Communicate with Children

Staff members must use their knowledge of child development to communicate appropriately with the children in their care. Be prepared to teach staff effective strategies for facilitating communication. When working with staff members in the classroom, observe as they engage with children to ensure they do the following:

Effective Strategies for Facilitating Communication

Use the menu at the left or the pager below to cycle through age-specific strategies

- Observe infants and toddlers for opportunities to communicate.

- Maintain eye contact with infants and toddlers.

- Imitate sounds infants make.

- Add more information to toddlers' comments (e.g., "Yes, that's green. It's a green and yellow dandelion.")

- Interpret communication for other infant or toddler peers (e.g., "Jamal looks really interested in what you're doing. I think he's asking to play with you.")

- Use new and interesting words.

- Sing songs and say rhymes frequently.

- Read to infants and toddlers.

- Follow infants' and toddlers' cues.

- Ask children meaningful questions about their actions, interests, events, or feelings.

- Read frequently and offer opportunities for children to be active in the reading and retelling of stories.

- Embed language games, songs, and rhymes into everyday routines.

- Provide frequent language models throughout the day; use rich vocabulary.

- Follow children’s leads, cues, and preferences.

- Include new words in conversations.

- Incorporate alternative ways and systems of communication based on children’s individual needs (e.g., using pictures or visual cues to foster communication).

- Communicate respectfully with school-agers; value their feelings, thoughts, age, and intelligence.

- Respond truthfully to school-agers' questions even when the question is difficult.

- Practice patience with slang or language that school-agers are adopting from TV or peer groups.

- Act as role models and respond to school-agers' conversations about text messaging, social media, and other electronic communication by discussing strategies for safe technology use.

- Practice active listening to indicate that you are paying attention and understanding what school-agers have to say.

Promoting Communication for All Children

You must prepare staff to support the communication needs of all children. Language development will be different for each child in your program, and the ways children communicate are strongly shaped by the people in their daily lives. Adults are the most influential models young children have. Staff members play a key role in fostering the language and communication skills of all children in your program. They may need extra support for children who have developmental delays or identified disabilities.

Children who have developmental disabilities may express language and communication differently. For these children, you may have to help staff adapt the curriculum, environment and experiences to enable them to be successful. For example, you might develop a simple picture board that staff could use to help children say “More please” at snack time.

Some children in your programs may have conditions that affect their language and communication development, including developmental delays, autism, neurological and perceptual disorders, or vision, hearing, speech, or language impairments. Children with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or Individualized Family Service Plans (IFSPs) have a specific plan to help them meet their personal goals, and very often these children will need changes or adaptations to curriculum, classroom environment, and daily routines.

Children with autism or developmental disabilities may have difficulties with communication. While some children may be able to engage in play and other experiences with verbal prompts and directions, other children may need visual supports that will make activities, routines or instructions meaningful and easier to understand.

Other children may need different supports. For children with hearing impairments, you may have to work with staff to make sure they adjust the speed or sound of their voices (speaking more clearly or at a slower pace). Children with visual impairments may use Braille, large print, or big books, so you may need to assist your program with purchasing. Other children may require assistive technology. This may include communication devices that enable them to explore their surroundings and interact with others.

Ways you can help staff members support the communication of all children:

- Create scripted stories about difficult routines and teach staff members how and when to read it to a young child. You can find downloadable samples at http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/resources/strategies.html#scriptedstories. Scripted stories can also be appropriate (with some modification) for older children in school-age programs. You might help a staff member create a photo book or video about a school-age child’s routine, or you could work directly with the school-age child to develop communication tools that will help them. For example, you might help staff members or a school-age child develop a checklist about the routines in the school-age program.

- Work with special education or early intervention professionals to access and provide training on assistive technology or other technology the child needs.

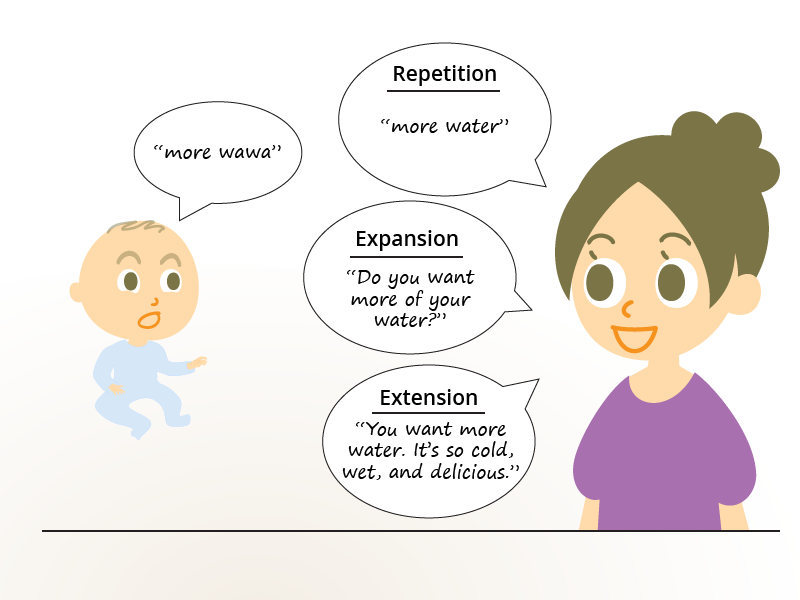

- Provide training on common language techniques. You can teach staff members to repeat, expand, and extend children’s language. For example:

Observe staff members regularly and provide feedback on the way they are using language with all children.

- Have problem-solving conversations with staff members when there is an issue. If a school-age child’s speech is difficult to understand, for example, brainstorm with staff members about ways to ensure that child is a successful communicator in the program. Observe in the program and act quickly with staff members if you see any signs of teasing or bullying. You might lead programs with staff members, families, or children to teach ways to embrace and respond to differences in a respectful way. Consider reviewing the Anti-Bias Curriculum for strategies you and staff members can use to foster an understanding of differences related to language, ability, culture, and other aspects of human diversity.

- Remember to encourage staff members’ efforts and successes. It can be scary for staff members to try something new or to communicate in new ways with a child or family. Celebrate small successes and encourage them to be persistent.

Model

You are a role model for communication in your program. The following strategies will help staff members see the strategies they should use in their own work:

- Talk to children and families every day. Greet children by name when they come in the door. This can be challenging in large programs, but you should make an effort to know as many children and families as possible. By doing so, you will help them understand who you are and what your role is. This will also create a more welcoming environment in your program.

- Be an active observer during your visits to classrooms and programs. Get involved and engaged to the maximum extent that you and staff members feel comfortable. Model communication strategies for staff members. Sit on the floor with infants and talk to them. Notice and comment on objects in the environment or things you see infants attending to. In preschool classrooms, model rich vocabulary when you talk to children. During experiments, comment on children’s predictions. Describe the structures children have built in interesting ways (“You used three cylinders to hold up the structure. It looks very sturdy.”). Ask school-age children about their interests, clubs, sports, or community events. Have natural conversations while you move around the program. Learn about popular media or events that are likely of interest to school-agers. Show an interest in what they care about or are learning in school.

- Be a reader. Talk with staff about books or articles you have read. Write a special note and share something you think a staff member might like to read. These can be professional books or recreational. Start a staff book club. Talk with school-agers about books they are reading. Encourage staff members to read along with the school-age children and discuss the books.

- Take an inquiry stance. Ask lots of questions and try to understand staff members’ and families’ perspectives.

As you move through the program and interact with staff members, watch staff members’ interactions with children. Look for signs that staff members understand child development and have realistically high expectations for children’s communication skills. Take a look at the following scenarios and think about what you see. What would you say and do in each case?

Communication Contrasts: Meals for Infants and Toddlers

Communication Contrasts: Meals for Preschool & School-Age

Explore

You probably spend much of your time observing adults or observing children whom adults have concerns about. It can be a good exercise to spend some time watching children and staff members engaging and communicating with each other. Watch this video of a school-age boy with communication challenges. As you watch, use your knowledge of child development and practices to support children with special communication needs. What would you talk with the staff member about? How might you apply your thoughts from this activity to staff members who work with younger children? Use the Observing Communication Activity to answer the questions and then review the suggested answers.

Observing Communication: Peer Communication

Apply

Here you can find a Milestone Guide about how children develop communication skills from birth through age 12. The tables are consistent with what direct-care staff members have read in their own courses. This document is intended as a reference for you or as something you can provide to staff members as a refresher.

Glossary

Demonstrate

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Developmental Milestones. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/NCBDDD/actearly/pdf/checklists/All_Checklists.pdf

Cooper, P. J., & Simonds, C. (1999). Communication for the Classroom Teacher. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

Derman-Sparks, L., LeeKeenan, D., & Nimmo, J. (2015). Leading anti-bias early childhood programs: A guide for change. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Diffily, D., & Morrison, K. (1996). Family Friendly Communication for Early Childhood Programs. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Hanft, B. E., Rush, D. D., & Sheldon, M. L. (2004). Coaching Families and Colleagues in Early Childhood. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2014). Family Engagement: Conducting a Family Survey.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2014). Principles of Effective Practice: Two Way Communication. Retrieved from https://www.naeyc.org/principles-effective-family-engagement

National Communication Association (2014). What is Communication? Retrieved from https://www.natcom.org/discipline/

Siegel-Causey, E., & Guess, D. (1989). Enhancing nonsymbolic communication interactions among learners with severe disabilities. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.