- Describe features of school-age environments that support children’s cognitive development.

- Discuss how children and youth explore their world and the opportunities for problem solving that are presented through new discoveries.

- Prepare a list of materials to spark cognitive development for school-age children in your program.

Learn

Know

The Third Teacher

The programs in Reggio Emily, Italy are known for both their philosophical approach to education and the aesthetic appeal and power of the environments in which children learn. The Reggio Emilia approach is based on the principles of respect, responsibility, and community. These principles are developed through exploration and discovery in a supportive and enriching environment created based on the interests of the children. In Reggio Emilia programs, the environment is known as the third teacher because of its importance to development and learning. The environment communicates messages about who is valued in a space, how to interact with materials, and how to engage with others in a collaborative way. The environment should be responsive to the need for adults and children to construct knowledge together. According to the philosophy, the child’s first teacher is a parent taking on the role of active participant in guiding the education of the child. The second teacher is you, and the third teacher is the environment. It is the combination of a child’s relationship with parent, teacher, and environment that best promotes learning.

Just like adults, school-age children are affected by their environments. It is our job to ensure classrooms and other learning spaces for children make them feel welcome, secure, supported, and ready to learn. Your program environment should be organized yet flexible to school-agers’ changing needs. This will help maximize children’s engagement and learning.

As you learned in Lesson One, cognitive development is all about learning. When children discover something new, they usually look for an explanation to make sense of the new idea. Your job is not to provide children with all the answers to life’s questions. Rather, you should guide children to develop their own ideas and opinions about the world around them (Satterlee et al. 2013).

Environments and Materials that Promote School-Age Children's Cognitive Development

When you understand what interests and motivates the children in your program, you can purposefully create environments and choose materials that facilitate learning. Remember that children learn about the world around them in a variety of ways. Exploration and discovery are vital to school-age children’s cognitive development. Your program should provide children and youth with plenty of opportunities to engage in activities that promote exploration and learning in multiple areas including: math, science, social studies, language and literacy, art, and technology.

How you facilitate and nurture this active learning is extremely important. In other words, the way you structure and organize your environments and materials for children and youth can make a huge difference in their development. Your school-age environment should be organized in a way that it enables children to engage in meaningful learning. Think about the interest areas in your program space. When a child in your program enters a purposefully designed area, do they know what materials they can find there, the type of activity (loud, quiet, social, or solitary) that might happen there, the expectations for how to behave, and ways in which they can explore, learn, and have fun in the space?

Learning is both individual and social and it takes place within social and cultural contexts. Therefore, you need to make sure your learning environment provides opportunities for children and youth to engage in individual work as well as meaningful interactions and collaborations with peers and adults in your program throughout the day. Consider the layout of your program space. How are your interest areas set up? Are there interesting and developmentally appropriate materials for children and youth to manipulate, explore, and learn from? When thinking about interactions between peers, how are you setting up the environment for these interactions to take place? For example, do you offer group projects to encourage children to work with their peers, share, and learn from each other? When disagreements arise among children, do you encourage them to talk to each other and try to solve a situation on their own while making yourself available in case they need support? The solution to undesirable behaviors if often discovered by changing one or more aspects of the environment. The materials and arrangement of the program space can play a major role in the relationships, interactions, and behaviors that occur between children in the program.

Promoting Exploration and Discovery in your School-Age Program

Exploration and discovery happen all the time when children pursue interesting ideas. As a school-age staff member, you can help children become explorers by asking meaningful questions to build upon their learning. The best questions to spark scientific discovery are open-ended questions such as, “Why do you think that happened?” and “What do you think will happen next?” These will start conversations that lead children and youth to think more deeply about their ideas. Additionally, you can promote exploration and problem-solving by providing school-age children with a balance of child-guided and adult-guided experiences. First, and perhaps most important, as a school-age staff member, you can model the creativity, thoughtfulness, and curiosity necessary for exploration. By showing their own interests in materials and experiences, adults can teach children about the value of exploration.

Exploration and Problem-Solving through Scientific Inquiry and Experiments

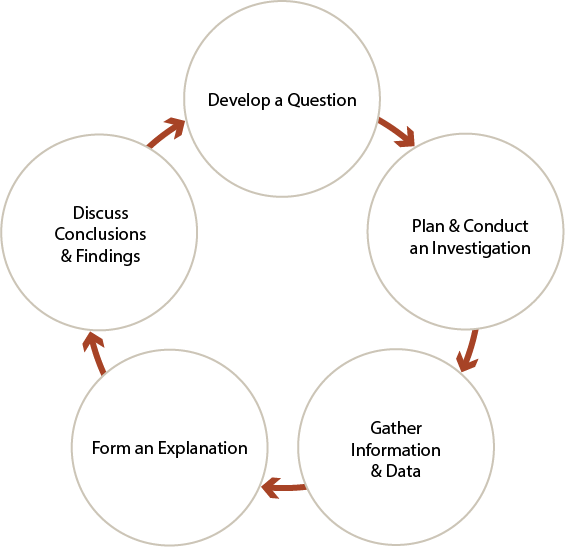

Curiosity is where thinking and understanding emerge. School-age children are captivated by natural phenomena. A simple walk outside reveals endless possibilities for explorations: an airplane flying through the sky, the color of plants, the buzz of cicadas, or the changing of the seasons all raise questions in school-age children. Your school-age program can guide children and youth to become critical thinkers by allowing them to follow their curiosities and develop scientific inquiries. Scientific inquiry is the process of developing a question and leading an investigation to gain information. Through scientific inquiries, children think deeply about a subject matter and experiment with ideas to develop a conclusion. Children should take ownership of their own inquiries. Your role as a school-age staff member is to guide children by providing suggestions and asking open-ended questions. Reaching a conclusion is not necessarily an important part of scientific inquiry. The process of investigating an idea and developing a plan is the primary goal. The process of forming and testing hypotheses, or guesses, enables children to practice valuable critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Dyasi, 2000).

The Steps of Scientific Inquiry

Environments and Materials that Address the Needs of All Learners

There are many things you can do to help all school-age children meet important learning goals. The first and most important step is to gather information about each child. You will need to know what the school-age child is able to do well and what seems to be challenging. You will also need to know what the school-age child likes and what is motivating for them. Gathering information will help you know the skills and strategies that are likely to help a particular child in your care.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL; CAST, 2011) is one strategy you can use. UDL helps all people learn and be successful in their environments. There are examples of universal design all around us: audio books, curb cutouts for strollers and wheelchairs, keyless entry on cars, and electric can openers. Many of these tools were developed for people with disabilities, but they make life easier for all of us. School-age staff members can use the principles of UDL to help design accessible and supportive school-age programs. Some examples of what you can do in your program space to support school-age children with special learning needs are: providing agendas (with or without pictures) of the activities that students will participate in, providing multiple ways for students to learn information (e.g., reading a book, watching a video, using the internet to research a topic), using materials in a different language, or sharing vocabulary words with school-age children before reading them a story. You can find additional examples demonstrating the use of UDL in the next lesson in this course.

The figure below shows three strategies for using UDL and offers examples of each.

Representation

How adults display information and provide directions

- Use objects, pictures, text

- Vary font size, volume, colors

- Offer tactile, musical, or physical variation

Expression

How children respond and show what they know

- Choice of text, speech, drawing, music, sculpture, dance

- Help with goal setting

- Provide checklists and planning tools

- Use social media

Engagement

How children become interested and motivated to learn

- Use child preferences

- Offer choices

- Vary levels of novelty, risk, and sensory stimulation

- Encourage peer learning

- Provide individual feedback

Including All School-Age Children in Learning Activities

One of the best things that you can do is actively include all school-age children in activities. Children with special learning needs or those learning English may have a hard time joining classroom activities because they may be unsure about what to do. Consider some of these ideas to help include all children:

- Observe school-age children working in small groups and make sure that children are not involuntarily excluded from activities.

- Before you begin an activity, think about what might be hard for a school-age child, such as using scissors, and be prepared to help that child complete the activity or provide a variety of options to complete the task (different types of scissors, a paper cutter, etc.).

- Use curricula expectations to teach school-age children about including everyone.

- Model how to can include others during collaborative learning activities.

- Provide behavior-specific praise to school-age children when they try to include others.

- Select books school-age children with diverse learning needs can read independently.

- Provide school-age children with different options for completing a task or activity. For example, children could paint pictures, put on a play, create a computer presentation, or write a report.

It is important to understand the idea of equity over equality in the program setting. The issue of fairness often becomes a worry for teachers and staff. Equality means providing equal support, materials, and expectations to all children. Equity means offering individualized support to children to address possible barriers. Equality means providing the same for everyone and equity means providing everyone with what they need to be successful. As a teacher or staff member, you should know the strengths and needs of all children and know how to provide individualized support to each child.

Another way to support school-age children and youth with special learning needs is differentiation. Differentiation allows school-age children with special needs to participate in different activities based on their skills and abilities. Differentiation works well with UDL. When differentiating activities, you can differentiate the content, product, or process. See the table below for suggestions of differentiating in your program.

Differentiate | Definition | Activities |

|---|---|---|

Content | What the school-age child needs to learn. |

|

Process | How the school-age child learns content. |

|

Product | How the school-age child demonstrates the content or skills learned. |

|

Reflecting on Your Own Practices

It is important to recognize the messages you send in your school-age program. Sometimes biases sneak into our environments, materials, or interactions. Awareness of your own bias is an important step in supporting development. Think about which of the following biases might be in your own program:

- Biased language. Language can send stereotypical gender messages. Adults might call children "baby girl," "big boy," or "cutie" rather than their given names. Staff might encourage girls to "be careful" while saying "boys will be boys." To fight this bias, you could encourage peaceful solutions for all children (avoid directions like not hitting girls or not hitting kids with glasses). Be sure to comment equally on youths' appearances and accomplishments. Consult the Creating Gender Safe Spaces course in the Virtual Lab School to learn how to support all children’s healthy gender identity and development.

- Stereotypical activities. Youth are often encouraged to play and engage in activities that are stereotypically related to a specific gender (e.g., girls engage in knitting and boys learn to code). Make sure youth get equal access and encouragement for all activities, such as woodworking, music, science, theater, dance, etc. Comment on the child’s actions during an activity or experience rather than your personal evaluation or cultural expectations.

- Biased materials. Sometimes posters and materials for the program present stereotypical images (e.g., Native Americans in "war paint," an all-male construction crew). Make sure the images in your program show men and women equally in a variety of professions. Make sure drawings or photos of people with disabilities are respectful images. Include books that show different ethnic backgrounds, social classes, and family structures.

There are many ways you can enhance the curriculum to improve children's understanding and acceptance of culture. The following are some examples (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2010):

- Classroom props or materials: Include props from a variety of cultures. Books, dramatic play clothes or other props, furniture, and musical instruments can all reflect experiences from around the world. Art materials should include a range of materials for representing skin tones and various artistic styles, fabrics of various patterns, and books about art around the world.

- Bulletin boards and displays: This space can be used to reflect and respect family traditions. Ask families to bring in pictures or other items for the board. Children and youth can spend time researching their own or another culture and documenting what they have learned.

- Class books or biographies: Books about children in the class document the real experiences of children and families. Encourage children and youth to create pictures, drawings, and text about their lives, ideas, and families.

- Family stories: Provide families with materials and instructions for creating a Family Book. Families and children can work together to talk about and record their family history and daily life. This can be a great way to introduce children and families to one another.

- Storytelling: Encourage grandparents or community elders related to children in your program to share stories of their childhoods with your program. These can be recorded or transcribed to create keepsake books for the program.

- Messages from home: Using a tape recorder, encourage family members to record a brief message in their home language. This can be played for a child when he or she is upset or homesick.

- Music: Include music tapes or CDs and songs from different cultures during music time.

- Field trips: Visit community cultural landmarks. Go see a dance troupe, play, or musical performance that will broaden children's cultural perspectives.

- Collaborative work: Encourage children to work together in groups. This may minimize the pressure on a child who is learning English. It also exposes children to a variety of ideas and encourages creativity.

- Snacks and meals: Invite families to share a traditional meal or snack with the children.

See

Promoting Exploration and Discovery

Do

There are many ways that you can support cognitive development through your environment and the materials you offer. You can:

- Provide thought-provoking materials and challenging games for school-age children to complete if or when they have some downtime.

- Provide snacks or other healthy food to ensure that children are ready to learn.

- Provide a clean and safe space where children feel productive.

- Provide a variety of developmentally appropriate and culturally diverse books for school-age children to read.

- Model the values of caring, respect, honesty, and responsibility.

- Make sure that the space is culturally sensitive and that there are no negative portrayals of different genders, races, or ethnicities.

- Develop rules and expectations collaboratively with the school-age children in your classroom.

- Ensure that the space reflects the needs and interests of the school-age children.

- Provide spaces where school-age children can relax or de-stress.

- Allow the school-age children to design or personalize part of the space.

- Implement activities where children and youth can use their strengths and abilities.

Explore

People of all races, cultures, ethnicities, ages, genders, and abilities should be represented equally and appropriately in your program materials and space. Take some time to look through the books, toys, and materials that are in your program space or classroom to ensure that children and families from diverse backgrounds are represented. Complete the Culture and School-Age Children’s Literature activity. Use this activity to review children’s books for common stereotypes and broad generalizations. Share your results with your trainer, coach, or administrator.

Apply

There are many resources to help you address the needs of all learners in your school-age program. Use the Resources for Your School-Age Program handout to find ideas offered by websites, organizations, and journal articles to help you be more culturally competent and responsive in your program.

Using the idea of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), Sandall and Schwartz (2008) identify eight types of curriculum supports for children with special needs and children learning English. Review the Curriculum Supports for All Children activity to learn about addressing the needs of diverse learners.

Glossary

Demonstrate

CAST (2011). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.0. Wakefield, MA: Author.

Derman-Sparks, L., & Edwards, J. O. (2010). Anti-Bias Education for Young Children and Ourselves. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Eileen Allen, K., Edwards Cowdery, G. (2011). The Exceptional Child: Inclusion in early childhood education (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Gestwicki, C. (2016). Developmentally Appropriate Practice: Curriculum and development in early education (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, Inc.

Diem, K. G. (2004). The learn-by-doing approach to life skill development. New Brunswick, NJ:

Rutgers Cooperative Research & Extension.

Heacox, D. (2012). Differentiating Instruction in the Regular Classroom: How to reach and teach all learners. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing.

National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning (2015). Designing Environments. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/video/designing-environments

Dyasi, H. (2000). What children gain by learning through inquiry. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2000/nsf99148/ch_2.htm

Purdue University. (2002). Experiential learning. https://www.four-h.purdue.edu/foods/Experiential%20Learning.htm

Satterlee, D., Cormons, G., & Cormons, M. (2013). Explore the Great Outdoors with Your Child.

Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. https://www.naeyc.org/our-work/families/explore-great-outdoors

Scholastic (2020). Teacher and Principal School Report. https://www.scholastic.com/teacherprincipalreport/index.html

Simmons, H. & Lyon, L. (2010). Authentic Social Studies: Experiential & cooperative learning.

Tomlinson, C. A., (1995). Differentiating instruction for advanced learners in the mixed-ability middle school classroom. ERIC Digest ED443572.