- Identify behaviors that are typical for preschool-age children.

- Discuss the role adults can play when it comes to guidance of preschool-age children.

- Describe the importance of understanding culture-based behaviors.

Learn

Know

Children’s behaviors and adults’ responses to these behaviors have a powerful impact on children’s development. Learning to manage behaviors through positive guidance is crucial for children’s participation in school and home experiences and for their overall growth. Consider some of the children in your own life and the different behaviors they engaged in as they were growing up.

It is important to recognize that guidance is not something that adults do to children. Instead, guidance is a partnership that adults partake in with children. When adults have appropriate expectations for children, they are less likely to feel frustrated and behave in less desirable ways. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) refers to this as developmentally appropriate practice (DAP). According the NAEYC’s 2020 position statement, developmentally appropriate practice is defined as methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approach to joyful, engaged learning NAEYC states that to be developmentally appropriate, practices must also be culturally, linguistically, and ability appropriate for each child. Adults working with young children should:

- Acknowledge the multiple assets all young children bring to the early learning program as unique individuals and as members of families and communities

- Recognize and support each individual as a valued member of the learning community.

- Implement learning environments to help all children achieve their full potential across all domains of development and across all content areas.

It is important to remember that children are developmentally different from adults. Children’s limited reasoning ability combined with their limited experience can bring them to conclusions inconsistent with adult logic. Oftentimes, children may not realize they have done anything wrong, or the behaviors considered inappropriate by adults may actually be typical behaviors of young children. For example, preschoolers may speak during circle time without raising their hands, or they may talk over other children during a large-group activity.

Young children cannot think about what they have not experienced. This means they cannot predict what might happen if they do something dangerous (Fields, et al., 2014). They also struggle with empathy; they are unable to process the question, “How would you feel if they did that to you?” We cannot force a child to think in more complex ways than what is developmentally possible, but we can aim for just a little bit more maturity than the child currently exhibits to encourage further development.

A guidance approach to misbehavior encourages preschool teachers to consider each child’s misstep in judgment as an opportunity for learning. It is never appropriate or effective practice to ridicule or cause children emotional suffering because they caused conflicts that they have not yet learned how to manage. Adults and children must assume responsibility for misbehavior. It is your responsibility to teach children less-hurtful ways to manage conflict. Likewise, it is the child’s responsibility to gain skills from the experience and to learn less-hurtful ways of expressing anger.

What Behaviors are Typical for Preschoolers?

Similar to progressing through developmental stages, there are certain behaviors that are considered typical for specific ages as children grow. These behaviors, while expected, sometimes challenge adults. The chart below provides examples of some of these behaviors. As you read these examples, think about the children in your care and the ways you respond to some of their behaviors. Remember that just as with every aspect of development, individual differences exist when it comes to children’s responses or behaviors in response to certain events or circumstances.

| Age Group | Behaviors that are developmentally appropriate (or expected) but may challenge adults |

|---|---|

|

Preschoolers |

|

|

Young School-Age (some of these behaviors are also seen in preschoolers) |

|

Just as you do with milestones, think of these behaviors as points of reference to help you better understand children and their development, so you can be ready to meet their needs. These behaviors should be reminders or typical patterns of growth and development in young children. Use them to help you know what behaviors to look for, and at what age, as children mature. Even though these behaviors may be typical of many children in preschool, each child is unique. Your goal is to help all children grow and learn to their potential.

You should also remember that expectations about behaviors are driven by cultural values and preferences. For example, in some cultures, children are not expected to feed themselves independently until they are 3 or 4 years old. In other cultures, children are expected to start eating independently in late infancy and toddlerhood. In your daily interactions with children and their families, you should remind yourself that culture and family priorities influence children’s behaviors.

Why Do Children Engage in Challenging Behavior?

There are many reasons why children might engage in behavior that adults find challenging. Sometimes, challenging behavior is part of typical development. In all cases, however, a child’s behavior communicates a message. It is up to adults to learn the child’s “code” and interpret the message. Here are some messages a child’s behavior might send:

- I need your attention, but I do not know how to ask for it.

- I do not know what I am supposed to do.

- I need help.

- I am bored.

- I am lonely.

- I do not feel well.

- I am scared.

- I am tired.

- I do not want to do that, or I do not like that.

- I am overwhelmed.

Helping Children Learn to Manage their Behaviors through Developmentally Appropriate Strategies

The strategies listed below work best in the context of strong relationships with children in your classroom and are adapted from the Massachusetts School-Age Coalition and expand on early childhood work by Patricia Hearron and Verna Hildebrand (2013). You will learn more about these strategies in lessons Three and Four of this course.

Have appropriate expectations for children’s behaviors: Rules, expectations, or guidelines help create a positive social climate in your classroom and program. Consider involving the children in your classroom in developing rules and expectations. Limit the rules or expectations to a few key ideas that apply broadly. It is easiest to remember a few rules like, “Use walking feet” or “Use kind words.”

Manage space, time, and your energy: As a preschool teacher, you arrange and rearrange the physical space and the schedule of the day to meet children’s needs. An example is moving furniture to eliminate a large open space that children use for running. Another example is providing many activity choices so wait time is minimized or used productively. You should examine your environments (physical space and time) first when a child has a problem in the setting. The way you organize your time or space influences the kinds of decisions children make in your classroom.

Create experiences that engage the whole child: If children are bored, over-stimulated, or disinterested, they are likely to engage in challenging behavior. Busy learners do not have time for challenging behavior! Be an intentional teacher and observe children regularly to ensure they are using materials effectively and appropriately, and that your activities and materials connect to their interests.

Capitalize on your relationships with children: Guidance is based on relationships. It involves finding and recognizing the positive attributes of every child. Strategies for guidance develop as you get to know the children, observe them, and listen to them. Make sure you spend “neutral” quality time with children, just listening, playing, and enjoying time together.

Help children express their feelings: Adults who help children identify and express their feelings, nurture empathy. You might look at a child and say, “I see tears. I’m wondering if you are feeling sad about what just happened between you and Terese. Would you like me to help you talk to Terese about it?” You must also be genuine and model your own feelings. On a different occasion you might say, “I’m feeling a little bit frustrated that I can’t get this computer program to work. I’m going to go find someone who can help us.”

Notice and recognize children’s positive behaviors: An important part of positive guidance is encouragement. You should notice and describe accomplishments or positive behaviors. For example, you might say, “Jonah, I bet you are really proud of yourself for solving that problem.” Or “I noticed that you gave Sonya a turn on the computer. She really appreciated that.” You should stop and notice all the positive behaviors that happen in your daily interactions with children.

Provide short, clear directions to children: Use a neutral tone of voice and make eye contact when giving simple directions to children in your classroom. Check to make sure children understand what you told them. Make it a habit to tell children what to do instead of what not do to.

Provide choices: Whenever possible, offer children choices. This promotes independence and self-regulation. It also minimizes challenging behavior. Any time you have to say “no,” you might offer two acceptable choices to children. For example, you might say, “You have to use walking feet in here. But you can run when we go to the gym or when we go outside later today.”

Redirect children to appropriate behaviors: When a challenging behavior occurs, your job is to help a child get back on track. “No,” “stop,” and “don’t” do little to help a child know what to do. An example of a positive redirection is, “Keep the scissors in the art area” or “Walk in the hall.”

Facilitate social problem-solving: Help children learn what to do when they have a problem. You should help them learn to recognize their problem, come up with solutions, make a decision, and try it out. You will learn more about facilitating this process with children in Lesson Four.

Understanding Culture-Based Behaviors

Children learn behaviors in the context of their relationships with their primary caregivers and within their families and cultures. If you think about how diverse our society is, you can imagine that this diversity is also expressed in the ways children from different backgrounds learn how to express themselves, interact with others, and manage their behaviors and emotions. Consider, for example, eye contact. While in some cultures children are taught to avoid eye contact, other cultures consider eye contact an essential component of social interaction. Another example is that of personal space. You can think of this in the context of your own upbringing. Maybe you grew up in a family where there were a lot of children or other individuals in the home. As a result, you may have developed certain ideas about the significance of personal space and your ability to tolerate being really close to other individuals. Alternatively, maybe you grew up as a single child or with fewer children or individuals in your home. These experiences could have created a different set of views about personal space and being really close to others.

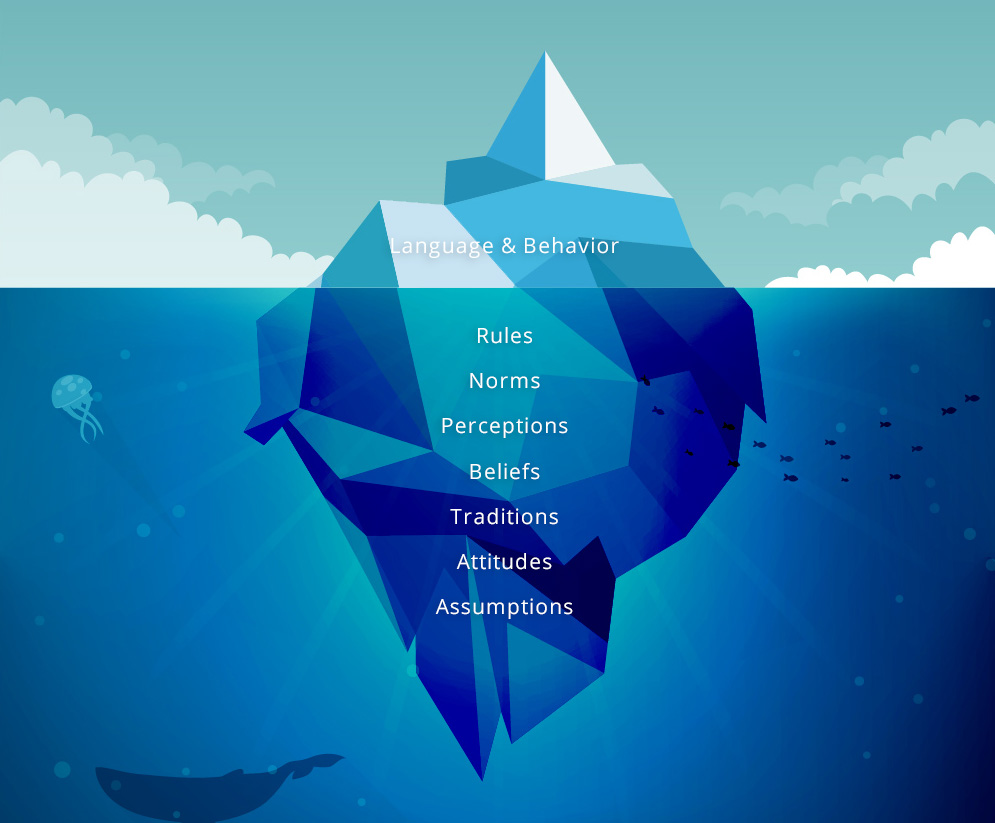

In your daily interactions with children and their families in preschool, it is important that you cultivate the habit of thinking about or addressing children’s behaviors while considering their home and community cultures. To help illustrate this idea, Santos and Cheatham (2014) used the iceberg analogy during the Head Start National Center on Quality Teaching and Learning Front Porch Broadcast Call Series. These researchers suggested that what we can see on top of the iceberg are children’s behaviors and language as expressed in their daily interactions with peers and adults in their classroom and school environment. These may be related to performing tasks independently, making friends, following directions, or being able to control themselves. What we cannot easily see beneath the iceberg, however, is what usually drives or explains some of these behaviors. Norms, perceptions, or traditions drive children’s behaviors, and therefore when children engage in certain behaviors, we should step back and think what may be causing these behaviors instead of rushing to make judgments about children or their families.

There may be skills or behaviors that are valued and reinforced within children’s homes and community cultures that are different from what is valued in your classroom and program. As a preschool teacher, you must be sensitive and respectful of individual differences when engaging with children in your care and their families. In other words, you have to look and think “beyond the surface” when considering children’s behaviors that may be challenging or different from what you would have expected.

See

Guidance and Preschool Children: Challenging Behaviors

Guidance and Preschool Children: Understanding Culture-Based Behaviors

Do

You should purposefully use specific strategies throughout your day to support young children’s guidance. Consider the following in your daily work with preschoolers:

- Spend time building relationships with the children in your care.

- Be responsive to children’s interaction attempts and build on what children are saying.

- Engage in frequent, developmentally appropriate social interactions with children and adults in your classroom throughout your daily experiences and routines.

- Follow children’s leads, cues, and preferences.

- Include emotion words in conversations with children.

- Make books that discuss feelings and social interactions available daily.

- Ask children meaningful questions about their actions, interests, events, and feelings.

- Encourage children to use their words and to talk to their peers when conflicts arise. Use developmentally appropriate language and provide conversation models and cues for children to follow if they need help to solve a problem.

- Ensure you are sensitive to children’s unique needs, experiences, and backgrounds.

- Reach out to children’s families and be responsive to their needs and preferences.

Explore

It is important to take time to learn how to reframe your thoughts about children’s behaviors. Negative thoughts about children’s behaviors can bring everyone down. Using negative explanations for why a child behaves in a certain way that may seem challenging can cloud your thinking about possible positive solutions. Having knowledge and understanding about why a child might choose to behave a certain way allows us to think of positive solutions; it helps us lift our negative mood. When we reframe our thinking, we can turn a negative into a positive.

Cognitive reframing is a way of viewing and experiencing events, ideas, concepts, and emotions to find more positive alternatives. Complete the Reframing Activity from the Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL). Add your own examples to the list. Then, share and discuss your responses with a trainer, coach, or administrator.

Apply

Use the resources in this section to learn more about supporting young children’s guidance and what you can do to support preschoolers in your care. Milestones of Social- Emotional Development is a comprehensive chart adapted from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use this information to learn about certain behaviors that are typical as children progress through developmental stages, and to plan your work with children in your classroom or program. The second document describes Culturally Sensitive Care and provides suggestions about building relationships with families of children in your care.

Glossary

Demonstrate

Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ). https://agesandstages.com/

Berk, L. E. (2012). Child development (9th ed.). Pearson.

Brown, W. H., Odom, S. L., & McConnell, S. R. (Eds.). (2008). Social competence of young children: Risk, disability, & intervention. Brookes.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Developmental milestones. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html

Dunlap, G., & Powell, D. (2009). Promoting social behavior of young children in group settings: A summary of research. Roadmap to effective intervention practices #3. University of South Florida, Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention for Young Children.

Fields, M. V., Merritt, P. P., Fields, D. M., & Perry, N. (2014). Constructive guidance and discipline: Birth to age eight. Pearson Higher Ed.

Gartrell, D. (2012). Education for a civil society: How guidance teaches young children democratic life skills. National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Hearron, P. F., & Hildebrand, V. (2012). Guiding young children. Pearson Higher Ed.

Kurcinka, M.S. (2015). Raising your spirited child: A guide for parents whose child is more intense, sensitive, persistent, and energetic (3rd ed.). William Morrow Paperbacks.

Developmentally Appropriate Practice: A Position Statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. National Association for the Education of Young Children. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/dap-statement_0.pdf

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2012). Teachers' lounge: Determining if behavior is bullying. Teaching Young Children, 5(5), 34.

Sandall, S., Hemmeter, M., Smith, B., & McLean, M. (Eds.) (2005). DEC recommended practices: A comprehensive guide for practical application. Sopris West Publishing.

Santos R. M., & Cheatham, G. (2014). Front porch series: What you see doesn't always show what’s beneath: Understanding culture-based behaviors. Head Start Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center (ECLKC).

Trawick-Smith, J. W. (2014). Early childhood development: A multicultural perspective (6th ed.). Pearson.