- Describe how to gather information and design program-level plans and procedures to support staff in addressing individual children’s persistent challenging behaviors.

- Facilitate meetings with families to discuss a child’s challenging behavior and how to create behavior support plans.

- Create a resource document that includes installation resources, community-based resources, and web-based information about addressing children’s persistent challenging behavior.

Learn

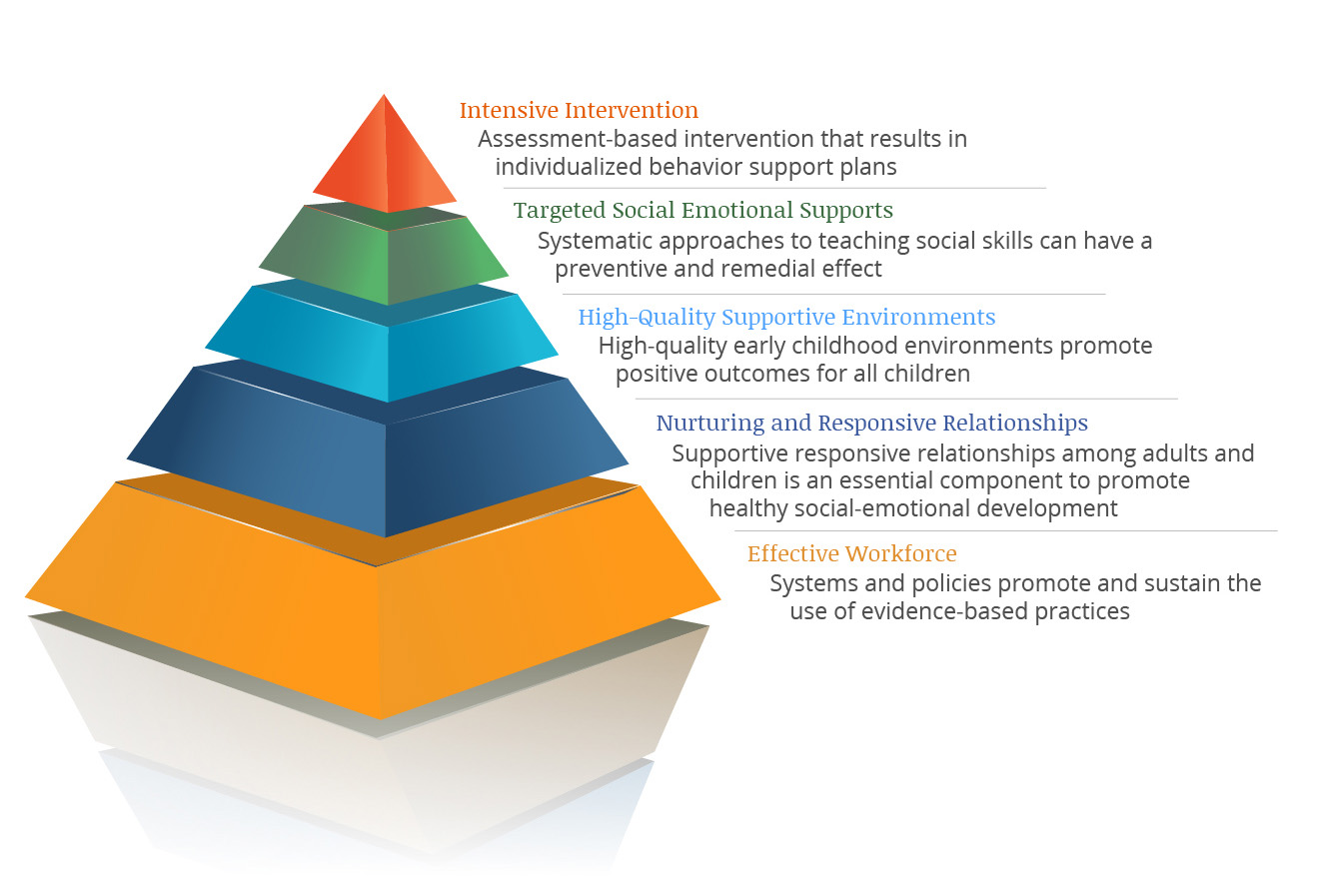

In Lesson Three, you were introduced to the Pyramid Model as a visual guide to thinking about the implementation of a quality program and its impact on the social-emotional growth and development of children. You learned that, as the manager, you are a key person in the implementation of the various components of the model and that your support and supervision of staff ensure that program policies are followed with regard to positive guidance practices. In this lesson, you will learn how your role as a leader greatly affects the ability of your program to serve children who engage in persistently challenging behavior. These are the small number of children who are in the top part of the pyramid (the red area).

The majority of children who attend your program respond to the staff’s positive guidance principles used to create a warm, nurturing climate. When a child does not respond to these principles and rather engages in persistent challenging behavior, it affects the child, other children, and staff members. Research has shown that Positive Behavior Intervention Support (PBIS) is an effective way of developing individualized plans to address children’s persistent intensive challenging behavior that “reduces challenging behavior, enhances relationships between adults and children, and generally helps caregivers and children experience an improved quality of life” (Hunt and Hemmeter, 2009, p. 9).

What Do We Mean by Persistent Intensive Challenging Behavior?

The Center for Social Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) defines challenging behavior as:

Any repeated pattern of behavior that interferes with learning or engagement in positive interactions with peers and adults.

Behaviors that are not responsive to the use of developmentally appropriate positive guidance procedures. Examples include prolonged tantrums, physical and verbal aggression, disruptive vocal and motor behavior, property destruction, self-injury, noncompliance, and withdrawal. Challenging behavior typically results in the child gaining access to or avoiding something or someone.

What is Positive Behavior Support?

- An approach to changing behavior

- Based upon humanistic values and research

- An approach for developing an understanding about why the child has challenging behavior and teaching the child new skills to replace that behavior

- A holistic approach that considers all of the factors influencing a child, family, and the child’s behavior (health, settings, communication skills, etc.)

As the program director, you must create program-level plans and procedures for referring a child who has persistent challenging behaviors. You may create a checklist or form that a teacher can complete in order to describe what the challenging behavior is and what steps have been taken to address the behaviors. A team approach must be taken to successfully address persistent challenging behavior. You are a critical member of the behavior intervention team. You will share information with the family, convene and facilitate the team meetings, observe the child or youth, and assist your staff and the child’s family with accessing any agencies or other resources as needed.

Process for Creating an Individualized Behavior Plan

The following steps can be used for developing and implementing individualized behavior plans:

| Step 1: Establish a collaborative team and meet to identify goals |

| Step 2: Gather information (complete a functional behavior assessment) |

| Step 3: Develop hypotheses (best guess about the function of the behavior) |

| Step 4: Design a behavior support plan |

| Step 5: Implement, monitor, evaluate outcomes, and refine the plan in natural environments |

Step 1: Establish a collaborative team and meet to identify goals.

As the program manager, you are charged with calling together a team to work together to address a child’s challenging behavior. Potential team members are the family, staff members, trainers and coaches, community mental health worker, and other specialized therapists. Everyone on the team helps to collect/gather information about the behavior.

Step 2: Basic Functional Behavior Assessment Process

Functional Behavior Assessment: Process that identifies specific target behavior, the purpose of the behavior, and what factors maintain the behavior that is interfering with the child’s progress

To understand the child’s behavior, the adults on the team (including the family) complete a functional behavior assessment. You might assist a behavior consultant to help complete the functional behavior assessment.

- Define the behavior in observable and measurable terms.

It is important that the staff member who refers the child to the team is able to clearly define the behavior in observable and measurable terms. Example: Tim uses verbal aggression (threats; name calling, swearing) with peers and adults when he has to wait for a turn to use a tricycle on the playground. - Ask about behavior by interviewing the family, staff and the child (if appropriate)

- Specify routines and summarize where and when behaviors occur

- Observe the child’s behavior during routines in natural environments (home, school, community).

Step 3: Develop a Hypothesis statement: a final summary of where, when, & why the child’s behaviors occur

The team uses the information gathered from the above interviews and observations to develop the functional behavior assessment. A hypothesis statement is written. The following is one example of a hypothesis statement:

“In group play situations (outside play), Tim uses verbal aggression (threats, name calling, swearing) to obtain a tricycle on the playground. When this occurs, the peer gives Tim the tricycle or an adult intervenes and provides Tim with excessive negative attention.”

- What triggers the behavior? Group play situations outdoors

- What is the challenging behavior? Verbal aggression (threats, name calling, swearing)

- What maintains the behavior? Peer gives Tim the tricycle; adult provides excessive negative attention

Step 4: Develop a Behavior Support Plan

When all of the observations, interview data, and any other pertinent other information are gathered, the team then meets to develop an individualized behavior support plan that incorporates prevention strategies and teaches the child replacement behaviors that will take the place of the challenging behavior.

The Behavior Support Plan includes the following components:

- Behavior Hypotheses - Purpose (function) of the behavior; this is the team’s best guess about why the behavior occurs

- Prevention Strategies - Ways to make events and interactions that trigger challenging behavior easier for the child to manage

- Replacement Skills - New skills to teach throughout the day to replace the challenging behavior

- New Adult Responses - Adults’ reactions to the challenging behavior which ensures the challenging behavior is not maintained and the new replacement skill is used.

The team should address all the variables that could occur (health, transitions, sleep, etc.) and think creatively about prevention strategies and replacement skills.

Example: Since the function of Tim’s challenging behavior is to obtain something (the tricycle) some prevention strategies might be:

- review playground rules individually with Tim before going outdoors

- use choices and child interests to distract or support Tim during times when all the tricycles are being used by other children (make sure the choices are ones Tim likes)

- use a timer to signal when Tim can have a tricycle

Teaching Replacement Skills

Teaching replacement skills provides Tim with an alternative behavior to his challenging behavior. Here are some important points about teaching a child replacement skills.

Replacement skills should be:

- Efficient and effective (i.e., work quickly for the child)

- Consider what the child already has

- Make sure any reward for appropriate behavior is consistent.

- Identify an acceptable way for the child to deliver the same message.

- Make sure the new response is socially appropriate and will access the child’s desired outcome

Replacement Skill Instruction Procedures:

- Select a skill to teach

- Teach skills intentionally using planned procedures

- Teach replacement skills during time the child is NOT having challenging behavior

- Teach throughout the day

New Adult Responses to Challenging Behavior

Adults need to intentionally plan how they will respond to Tim’s challenging behavior that will make it ineffective in obtaining adult attention. The adults need to be sure to encourage Tim’s new appropriate skills and pay more attention to Tim’s use of socially appropriate behavior than to his challenging behaviors.

Here is what Tim’s Behavior Support Plan Chart looks like after the team brainstorming meeting:

| Trigger | Behavior | Maintaining Consequence |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Prevention Strategies | Tim’s New Skills (Replacements) | New Adult Responses |

|

| To Tim’s Challenging Behavior:

To Tim’s New Replacement Skills:

|

Implement, Monitor, Evaluate Outcomes, and Refine The Plan in Natural Environments

When planning and implementing an individual behavior support plan, it must be easy for everyone to use (including the child’s family). Data must be collected and shared to determine if the plan is effective. There are many formats for collecting data. The handout, Guidance Data Collection (see the Learn Section) provides information about ways to collect data. Being an outside observer, the manager could be responsible for taking data and observing to see if the team is carrying out the prevention strategies and teaching the child the replacement skills. You are a key support person to staff members. Make it a point to be available for consultation as they learn to implement the plan.

The behavior plan needs time to work (teams should meet after three weeks to check in on how the plan is working)—often staff are looking for “quick fixes” for persistent challenging behavior but quick fixes typically do not occur. Sometimes the child’s challenging behaviors may increase before they decrease, and this can be discouraging for teachers and parents. Your positive attitude and willingness to support the team through this behavior change process is vital to its success.

It is good to create a support plan checklist to determine if the plan is being followed. The team needs to meet and review the data you have collected. Being the manager also means you know when the team needs outside professional support to create and sustain a behavior plan for a child. Your network of installation and community resources may be called upon to assist in the development and monitoring of individual behavior support plans.

If the child or youth with challenging behavior is receiving behavior support through his or her public school, you may, with the family’s written permission, seek consultation from the school staff to assist with the child’s challenging behaviors in the youth program. For children who receive behavior support in school, it is important that there be consistency across settings (including home and child care).

It is beyond the scope of this lesson and course to teach you everything you need to know about positive behavior support planning. However, there are excellent resources available to help you do this important work. For early childhood programs, you can explore the resources available through the National Center on Pyramid Model Innovations (or NCPMI, which merged with the Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention, or TACSEI): https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/

Difficult Conversations: Referring Families to Community-Based and Online Resources on Child Guidance and Behavior Issues

You may have some difficult conversations with families about child guidance and behavior issues. It is important that you approach conversations with family members as a listener who wants to hear the family’s perspective on their child. Families do not want teachers or program managers to approach them in a judgmental manner or question their parenting abilities. All families have strengths, and as partners in caring for their children, program staff should acknowledge the hard job parents have raising their children.

It is never easy to talk to families about something they hope to never hear about their child. It is important that a strong relationship is well established between you and the family through ongoing communication during regular daily interactions. These conversations may include suggestions of community-based resources that can provide more intensive interventions. Jodi Whiteman (2013) lists some helpful strategies for having difficult conversations:

- Ask questions and listen. Wondering together with families demonstrates equality between the professional and the child’s family. This also shows your respect for the family. For example: “I was wondering if you have noticed Alyana’s hesitation to climb on the playground equipment? Is there something we should be aware of in order to help her feel more secure on the playground?”

- Active listening. Active listening involves paying full attention to what the other person is saying and letting them know you understood their message. (“You told Alyana not to climb on playground equipment because you heard that a neighbor’s daughter fell off a swing at the park and had to get several stitches.”)

- Show empathy. Showing empathy involves your willingness to accept another person’s experiences and feelings. (“I can imagine it is scary to think that Alyana might get hurt on the playground equipment because of what happened to your neighbor’s daughter.”)

When referring a family to an outside agency or other resource, it is important to have the correct information about the agency’s purpose and services. It is helpful if you have a personal contact at the agency so there is a name the parent can use when initiating contact. For some families, it may be helpful to offer to go with them if they are unsure about how to approach an agency.

In your outreach to families, you can maintain a parent resource list that includes installation and community agencies. This list should be available in the family corner on the program’s website. You can also provide examples of parent resources about behavior in the program newsletter. Families are an integral part of your program’s community. You and your staff are collaborators with families in their most important task—raising their children. As you build relationships with family members, the children will know that the adults in their lives are working as a team to provide them with loving care.

Engaging In Difficult Conversations With Families

The Importance of Positive Child Guidance

Explore

Reflect on the process of creating and implementing an individualized behavior plan for a child. What resources and training do you believe are necessary for you to feel confident and competent in facilitating a behavior intervention planning team meeting? What training on individualized behavior supports is available to you and your staff (look for webinars and other web-based or conference-based opportunities for staff development)?

These links may be helpful in selecting articles and books for the Family Corner and/or Staff Resource area. Think about planning a joint training about challenging behavior that could include staff from other programs.

- NAEYC - Guidance and Challenging Behaviors

https://www.naeyc.org/resources/topics/guidance-and-challenging-behaviors - Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) focuses on promoting the social-emotional development and school readiness of children from birth through age 5. The website offers resources, in English and Spanish, for families, trainers, teachers, caregivers, and states. Also includes training modules about infants/toddlers and preschoolers, and a module for parents.

http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu - University of Minnesota Center for Early Education and Development website has resources about positive behavioral support for young children who engage in challenging behavior. The website offers tip sheets, case study examples, information for parents, and guidance on building a technical assistance team

http://ceed.umn.edu/tip-sheets/ - Guidance Matters, a Young Children column by Dan Gartrell, discusses early educators’ use of guidance to foster young children’s development and learning. The column is published in the issues of Young Children, and an archive of the columns is available online.

https://drjuliejg.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/annotated-gm-columns1.pdf - National Center for Early Childhood Development, Teaching, and Learning (NCEDL)advances best practices in the identification, development, and promotion of the implementation of evidence-based child development and teaching and learning practices that are culturally and linguistically responsive and lead to positive child outcomes across early childhood programs. They also support strong professional development systems.

https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/about-us/article/national-center-early-childhood-development-teaching-learning-ncecdtl - National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations (NCPMI) creates free, research-based resources to help parents, caregivers, administrators, and policy makers apply best practices when working with children who have or are at risk for delays or disabilities. The website includes a glossary of terms, briefs on systems and procedures, and related links.

https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/

Apply

Think about resources for addressing children’s challenging behavior that you believe are most critical for you, your staff, and families to have. Download and print the Positive Behavior Support Family Questions and Answers attachment from the Center for the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL).

Use the information as a template and to develop your own family focused description of positive behavior support. Describe how you would provide access to those resources. Create an agenda for a team meeting that you would hold in order to begin the process for creating an individual behavior plan. What would be important to include on the agenda? Are there outside consultants that you would want to invite? What steps do you need to take to obtain parent permission to start the process of developing an individualized behavior plan for a child or youth?

Glossary

Demonstrate

Center for the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL). Retrieved from http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/

Hunter, A., & Hemmeter, M.L. (2009). Addressing Challenging Behavior in Infants and Toddlers. Zero to Three, 29(3), 5-12.

Lentini, R., Vaughn, B. J., & Fox, L. (2008). Creating Teaching Tools for Young Children with Challenging Behavior. Retrieved from https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/Pyramid/pbs/TTYC/index.html

Technical Assistance Center for Social and Emotional Development for Young Children. Retrieved from https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu

Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports. Retrieved from https://www.pbis.org/

Whiteman, J. (2013). Connecting with families: Tips for those difficult conversations. Young Children, 68(1), 94-95.