- Define family engagement.

- Model inclusive, welcoming, culturally sensitive, and responsive practices for staff to emulate.

- Identify the developmental stages of relationships and strategies for supporting staff through those stages.

- Utilize reflective supervision to support staff as they build and sustain relationships with families.

Learn

Introduction

Engaging the families your program serves is at the heart of the work you and your staff do every day. Engaging families is a goal of every program manager. When families are engaged in all aspects of your program, they feel more confident in your program and staff, and their children learn and perform better.

Family Engagement: What Is It?

What are your feelings about working with families? What do you enjoy about it? What seems difficult? While you may feel motivated to develop relationships with families and to support family engagement, it is common to feel more success in focusing on your direct interactions with children and staff members. It may not seem simple to combine these practices.

Family engagement has different meanings for different people. In many cases, it relates to an ongoing partnership between your program and families. Child development and school-age programs are committed to engaging and involving families in meaningful ways, and families are committed to actively supporting their child’s learning and development. The literature around family engagement highlights the following characteristics:

- Strong, trusting relationships between teachers, families, and community

- Recognition, respect, and support for families’ needs, as well as differences

- Strength-based partnership where decisions and responsibility are shared

- Activities, interactions, and support increase family involvement in their child’s healthy development

- Families take responsibility for their child’s learning

- Acknowledgment that family engagement is meaningful and beneficial to both families and the early care and learning program

It’s important to realize that family engagement can look different and take on many forms. What family engagement means and looks like depends on the unique characteristics and the individual comfort levels and understanding of each family.

To help make sure that families are committed to their child’s learning and engaged in the child development and school-age programs, families should be invited to participate at whatever level they feel most comfortable. Does participation mean monthly meetings or taking part in a parent advisory committee? (And are meeting minutes from the parent advisory committee shared with all parents?) Does participation mean donating cookies for a bake sale? Going on a field trip with the class? It is important for families to feel supported and recognized for the ways in which they are able and choose to participate and engage—from bringing their child to the program each day to sharing their concerns or serving on committees.

Importance of Family Engagement

Family engagement can benefit children, parents, families, teachers, and program quality in various ways. Can you remember what caring adults in your family, community or schools did to help you grow and develop?

Families are their children’s first teachers and they have a powerful effect on their young children’s development. Family engagement during the first years of life can support a child’s readiness for school and ongoing academic and lifelong success. Research shows that when children have involved parents, the results are very positive, especially over the long term (A New Wave of Evidence, 2002).

When families are involved in your programs, they may also feel more vested in what happens there and more competent in their role as parents. Through these interactions and relationships, families may learn additional strategies to promote development and learning at home. Such strategies include expanding children’s language, following their child’s lead in play, helping with homework, or responding calmly to behavior that challenges.

Taking a “Why Not” Approach

A family-centered practice that nurtures the development of respectful relationships honors the requests and preferences families have for their children. As Greenman said, “When parents ask us for a change in their child’s routine, a special activity, or a different way of doing things, we genuinely ask ourselves, why not?” This doesn’t mean that requests should be met with an automatic “yes,” as there are valid reasons in some cases that the answer must be “no.” Embracing a “why not” approach means that you and staff are open and flexible when it comes to addressing families’ requests. Just because something has not been done before does not mean it cannot be done. Think about a time when you had an idea dismissed before there was any discussion about its merit. How did this make you feel? Similar to families with unconsidered requests, you probably didn’t feel respected.

When staff see you taking a “why not” approach with families, they are encouraged to do the same. This approach can also lead to new ways of doing that be of benefit to everyone. Promoting family choice within the boundaries of the program is a tangible way to demonstrate respect.

Mutually Beneficial Relationships with Families

The development of mutually beneficial relationships is essential when it comes to engaging families. Families are more likely to get involved, share feedback, participate in decision making, and accept support when they feel connected.

Mutually beneficial relationships resemble a dance where each person takes their cues from the other person. It’s a flow of give and take where everyone is on equal footing. Mutually beneficial relationships are built on trust and take time to develop, however they are rarely conflict free.

The very nature of child and youth programs makes the development of these types of relationships more difficult. The term “partnerships on the run” describes the difficulty as most of the relationship building occurs at either drop off or pick up; neither of which are conducive for extended conversations or meaningful dialogue. Not to mention that everyone is busy juggling the demands of work and family. As a result, relationships can take longer to develop and this increases the chances for misunderstandings and potential conflicts to arise. You play a critical role in the development and sustainment of mutually beneficial relationships.

Relationship Development

Take a moment to consider your really close relationships and you will recognize that there was a process you went through to get to the point where you are today. Relationships take time, are often characterized by a series of ups and downs, and require frequent opportunities for communication. Your role is to help staff develop these types of relationships by using your knowledge of the development of relationships and the use of effective relationship-building strategies, such as reflective supervision.

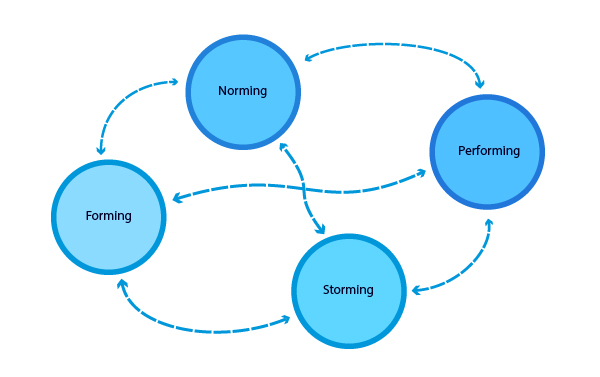

In 1965, Bruce Tuckman created a model of team development. Mutually beneficial relationships are an essential aspect of high functioning teams. His model has four phases: forming, storming, norming, and performing. He believed that these phases are necessary and inevitable for a team to come together, to face difficulties, and to work through problems to find solutions and achieve results.

Families are an integral part of your team and understanding how teams develop can help you as you support your staff in their relationships with families. Depending on the phase, staff may need more or less of your assistance and support. It’s important to keep in mind that teams will go through these phases many times or revert to an earlier phase as situations change.

This is only one model of team development; the business and leadership literature is full of other models you could consider. This particular model is concrete, simple, and easy to apply in your work with both families and staff.

Forming

In the Forming phase, you and your staff get to know the family while they get to know the program, your staff, and you. Families learn how the program operates as well as the rules and expectations. General information is shared and first impressions are formed. Generally, everyone is on their best behavior so there is little opportunity for conflict. This phase can be like a first date or a job interview. Generally, people are guarded — not wanting to do anything to jeopardize the relationship or leave a negative impression.

During the Forming phase, your role is to facilitate the development of the relationship to ensure a smooth transition for the family into your program. Parents can have a range of emotions from guilt to sadness when leaving their child in someone else’s care. Sometimes, parents may not even realize the depth of these emotions until they are expressed in an unexpected way. You can make sure the relationship gets off to a good start by making introductions, reviewing the family handbook, answering questions, checking in at pick up time, and validating their feelings of angst.

Storming

The Storming phase is characterizes by the differences in opinions and expectations that emerge as relationships develop. Different parenting practices or unrealistic expectations can lead to conflict. These conflicts are necessary to create change; so while they may be uncomfortable, they are important for the development of trusting relationships. The goal is not to eliminate conflict but rather work through it so everyone has a deeper understanding, tolerance, and appreciation of differing perspectives and viewpoints.

During this phase, your role is to be proactive in addressing concerns before conflict occurs and to be available to support families and staff when problems do arise. For example, a parent of a toddler may become furious when the child’s clothes are covered in paint. He vents his frustration by making some inaudible comment as he leaves the child’s classroom and then storms into your office. On one hand you have a teacher who recognizes how important art is to development and on the other, a parent who doesn’t want his child’s clothes ruined.

Without your guidance, this problem could fester or go unnoticed and become much more damaging to the relationship. Your ability to help each party share their differences in a nonjudgmental environment supports the resolution process and moves the relationship forward. In the example above, meeting with both the parent and the teacher to generate possible solutions, such as putting an oversized t-shirt on during messy activities, could resolve the issue. A systems approach might include asking families to identify on their entry questionnaire if they want special accommodations during messy activities, and if so instructions for providing additional clothing.

Norming

As problems arise and are resolved in mutually acceptable ways, relationships deepen. The Norming phase is characterized by more trust and openness in family-program relationships, which leads to respect and more give and take. As a result, people are able to work through their differences without assistance. For example, if one of your teachers talks with a parent about a behavioral concern, the parent may come to you to express his or her dissatisfaction with the teacher (storming). After the three of you meet, everyone agrees to try suggested strategies. Over time, the parent and the teacher are able to discuss concerns when they arise without your assistance.

During this phase, your role is to step back and allow the relationship continue to develop. There is always the tendency to want to jump in but it’s important that staff and families learn to work through conflicts on their own. While there may be incidents of “storming” from time to time, the need for intervention on your part diminishes.

Performing

In the Performing phase, families and staff are able to function independently. They have equal value and are equal partners. They work toward the same goals while understanding and respecting each other’s perspectives. There can still be disagreements from time to time, but instead of derailing the relationship, they strengthen it.

During this phase, you as a manager are a participant. Don’t get too comfortable, as there is most likely some storming going on in your program with other families as you read this. Hopefully, this model demonstrates that conflict is natural and important to the development of relationships, and while it can’t be eliminated, it can be managed. While this model was used in relation to families, it also applies to your staff relationships.

Reflective Supervision

Reflective supervision is one of the most useful approaches for supporting the cycles of relationship development as well as family-centered practices. Rebecca Parlakian, in her book, Look, Listen and Learn, identifies three building blocks of reflective supervision — reflection, collaboration, and regularity. Understanding and utilizing these three building blocks will help you as you support your staff in their relationships with families.

Reflection

Reflection requires taking a step back and examining your thoughts, feelings and reactions. Your role is to create an environment where families and staff feel emotionally safe so they can be honest about their feelings without fear of negative consequences. It’s important that you don’t take sides or cast judgment. Active listening and the use of open ended questions support the reflection process.

Collaboration

Collaboration emphasizes shared responsibility and decision-making. Your role is to step out of your comfort zone of control to support staff members as they step out of theirs. Collaboration is about supporting staff as they solve problems. Open communication and asking what-if questions supports collaboration.

Regularity

Regularity requires consistently scheduling plenty of time for reflection and collaboration can occur. Reflection doesn’t just happen during nap time and collaboration is more than sharing a conversation in the staff workroom. For reflective supervision to be effective, you must make it a time priority. The way you spend your time sends a message to your staff about what you value. Valuing this process supports your staff, your families and your program.

In Summary

Families are your partners, not simply because you say they are, but rather because you actively engage and communicate with them. Developing mutually beneficial relationships with families leads to true partnerships and it’s only then that meaningful engagement occurs. Your role is to help staff develop these types of relationships by using your knowledge of relationship development and by applying reflective supervision. You can also use the following strategies to help staff members welcome and involve families.

Model Welcoming Families

Begin by thinking about what it might mean for families and new parents to consider your program for their child. Families often experience uncertainties and feel scared when seeking a child development or school-age program for their child. You can do the following to help staff members support families during this sensitive time:

- Invite families to visit before their child’s start date. Be present to answer questions about the program’s curriculum and programming.

- Encourage staff members to send families a personal welcome note to each child who starts in the program. Provide the stationary and make sure staff members have protected time to write the notes.

- Share information with families about how they can participate in the program. Work with management and a family advisory group to brainstorm ways families might enjoy being involved.

- Provide tools or mechanisms for staff members to ask families about their child’s routines, strengths, interests, likes and dislikes.

- Learn about the home languages used in your program and help staff learn key words and phrases to use in the program.

- Survey families about their communication preferences. Work with management to ensure that an updated email communication list or phone tree is maintained for families that prefer those methods.

- Maintain a family bulletin board with information about current program activities, upcoming meetings and events, and community opportunities that are of interest to families.

- Display photographs of children and their families in program spaces– hang them on the wall where they can be seen or in durable photo books that children can hold and explore in the lobby.

Model Encouraging Families to Be Involved

Families want to be included and involved in child development and school-age programs. There are a number of ways to encourage and support family participation, such as:

- Inviting family members to share special talents (e.g., play an instrument, read a book, sing, engage in an art activity)

- Offering family members jobs (e.g., help repair broken toys, create books or special photo albums)

- Inviting families to observe their children with you or staff members

- Asking families to help plan activities of their choice based on their strengths and interests

- Creating and sending out a short survey to families asking about their ideas and suggestions for ways they might like to participate

- Scheduling opportunities for families to join their children breakfast, lunch, or snack

- Encouraging families to share suggestions or concerns with you

Within your program, there should be a specific plan as to how to engage families throughout the year. Though families’ participation is voluntary, it is your job to make them feel welcome by actively encouraging involvement. Program activities should reflect families’ interests and motivate them to participate. Additionally, your program may have a family involvement committee. This committee is composed of family members who encourage communication and involvement with the goal of strengthening and supporting the well-being of children and families. This committee is a resource and asset to your program as families may discuss issues or concerns and suggest changes to improve family satisfaction and involvement.

Explore

According to Jim Greenman, respect means accepting, as we do with children, that parents are individuals:

- Some will be friendly and outgoing; some won’t.

- Some will be forthcoming with information about the child and family; some won’t.

- Some will be interested in becoming involved in the life of the center; some won’t.

- Some will read newsletters avidly, come to meetings, bring changes of clothes, pay fees on time, never be late picking their child up; some won’t.

- Some will exemplify our own views about exemplary child rearing; some won’t.

- Some will be very grateful for the care their child is receiving and will let you know; some won’t.

- Some will feel guilty or sad about using child care; some won’t.

- Some parents, a few, will be very critical of care; some won’t.

Use this list to initiate discussion with staff as a way of exploring their feelings about family members who might exhibit some of the behaviors listed above. Encourage them to identify strategies for interacting with families who might seem picky or problematic. Staff could also role-play scenarios using the list above. The point of this exercise is to get your staff to understand that their feelings are natural but their responses may need to be tempered depending on the situation.

Apply

Watch the following video to hear about ways families are honored. They may describe things that are already being done at your program and there may be some ideas for you to try. There are many ways to honor and engage families. Including them in the planning process is one of the best ways to demonstrate your respect for them and their ideas.

From Our Hands To Yours

Glossary

Demonstrate

Gonzalez-Mena, J. (2008) Diversity in Early Care and Education: Honoring differences. New York: NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies.

Greenman, J. (1998). Places For Childhoods, Making Quality Happen In The Real World. Redmond, WA: Exchange Press Inc.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2011). NAEYC Position Statement: Code of ethical conduct and statement of commitment. Retrieved from http://www.naeyc.org/positionstatements/ethical_conduct

National Association for the Education of Young Children. Engaging Diverse Families.

Parlakian, R. (2001). Look, Listen, and Learn: Reflective supervision and relationship-based work. Washington, D.C: Zero to Three.

Program for Infant Toddler Care: www.pitc.org

Tuckman, B. (1965). "Developmental Sequence in Small Groups", Psychological Bulletin 63(384):99.

Zero To Three: www.zerotothree.org